In the 2020 election cycle, our staff and volunteers made more than 53 million voter-contact attempts and sent more than 21 million handwritten postcards. (Read our full Impact Report here.)

Our data department is at the center of our program design. Today’s blog post is by our Data and Analytics Director, Anastasia.

In February 2020, Progressive Turnout Project brought our more than 100 District Leaders from around the country to Chicago for a week-long training. We worked to prepare for the election ahead, learning about field tactics and canvassing best practices. None of us thought that in a few short weeks our world, and our work, would look completely different.

Everyone knows what happened next: we packed up our things, downloaded Zoom, and wondered how long this would all last.

Since 2015, PTP has focused on refining traditional door-to-door canvassing — long recognized as the most effective way to increase voter turnout, especially compared to expensive TV ads or much-maligned yard signs. Our 2018 canvassing programs increased turnout by an average of 10.4 percent.

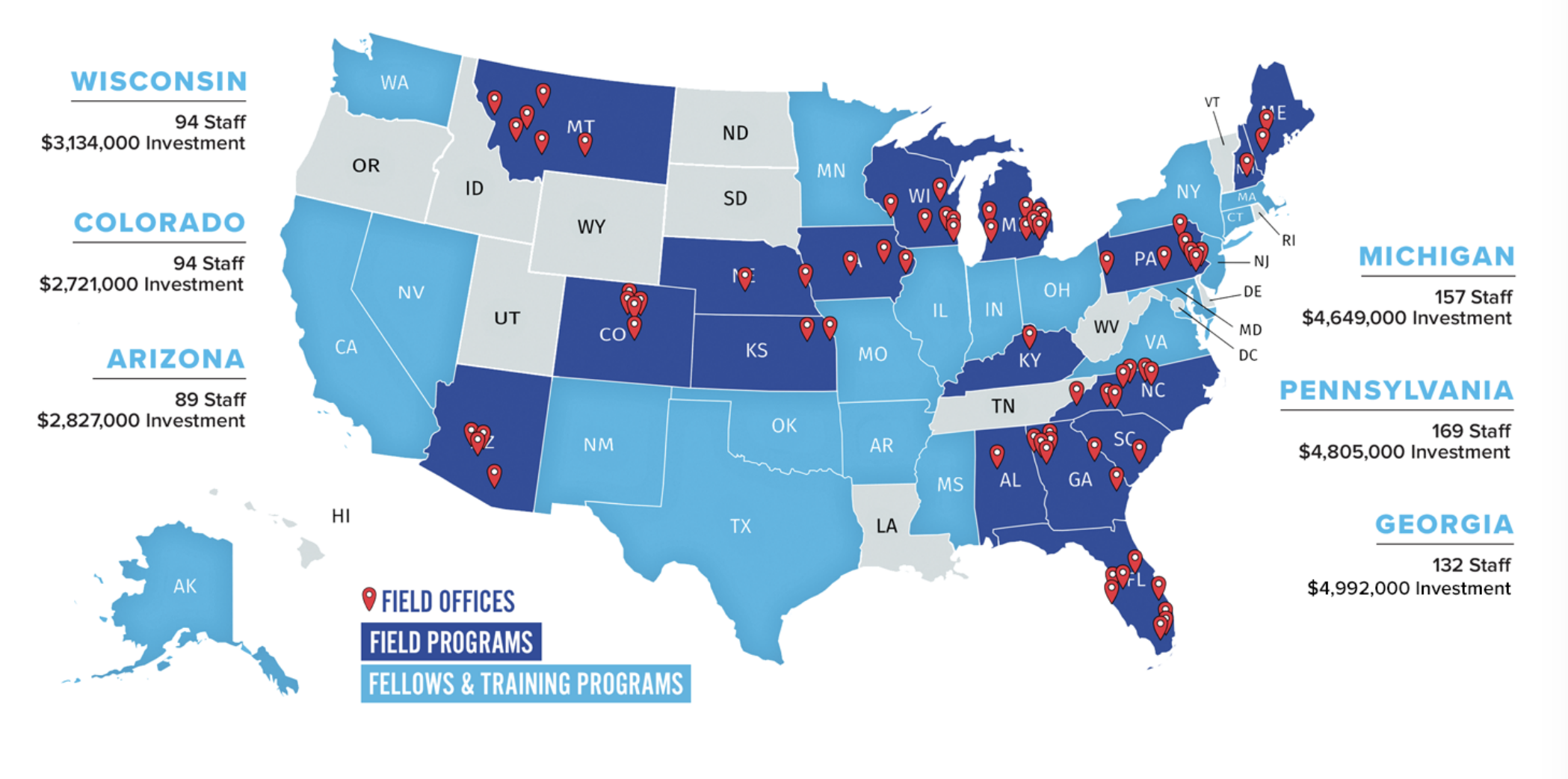

Our field program is specifically designed to reach infrequent voters by beginning early and making multiple contacts. We initially hoped that the pandemic would subside by our targeted start date in May (how naive!). But as June got closer, the situation got worse, not better. Also complicating matters: circumstances varied tremendously from week to week and among our 17 different states.

We ultimately determined that our in-person plan could not happen. For an organization grounded in door-to-door canvassing, it was difficult to determine where to go next — especially on such a short timeframe.

Eventually, we settled on phone calls as the best, safest way to replicate those two-way interactions we value with voters at the door. Along with personalized cards we sent to voters, we felt this was the best way to utilize our 1,200 staff members and connect them directly to voters. Other digital avenues did not provide the same reach or responsiveness as calls, and were unable to lead to those robust conversations that are key to our success.

We found ways to keep other important pieces of our programs, like commit to vote (CTV) cards and thank-you notes, even while our main form of contact had shifted.

On the data and analytics end of things, this experience was tremendously difficult, but the sudden shift taught us a lot. Some of these lessons may be specific to a (hopefully) once-in-a-lifetime pandemic, but others ought to be carried forward in future cycles.

With Election Day and Inauguration Day behind us, we returned to the data to see what worked and what didn’t. Here are four things we learned:

#1: You can call where you can’t knock (and vice versa)

When we made the shift to phones, our universe (that is, the group of voters we wanted to reach) stayed largely unchanged — except for two big things:

- We were no longer limited by geography. Since no one had to drive from a central office, we could target people all over our target states. This was an especially big game-changer in states with significant rural populations, like Georgia.

- Our universe was at the mercy of the phone numbers we had in VAN, the Democratic voter database. Luckily, there were a lot of those, but even then, there were plenty of people we had no way of reaching via phone.

The starkest difference from our in-person canvass universe was in urbanicity.

Urbanicity is a measure of how urban or rural someone’s address is, from one (most rural) to six (most urban). Our canvass universe was mostly fours and fives — a result of placing our offices with car-based canvassers in mind. But, when we switched to phones, our share of rural voters (ones and twos) went up nearly threefold:

While no group of voters is “better” or “worse” to reach, it was a silver lining to see this group of voters who are otherwise challenging to canvass — because of low density, more remote areas, etc. — become a key part of our universe.

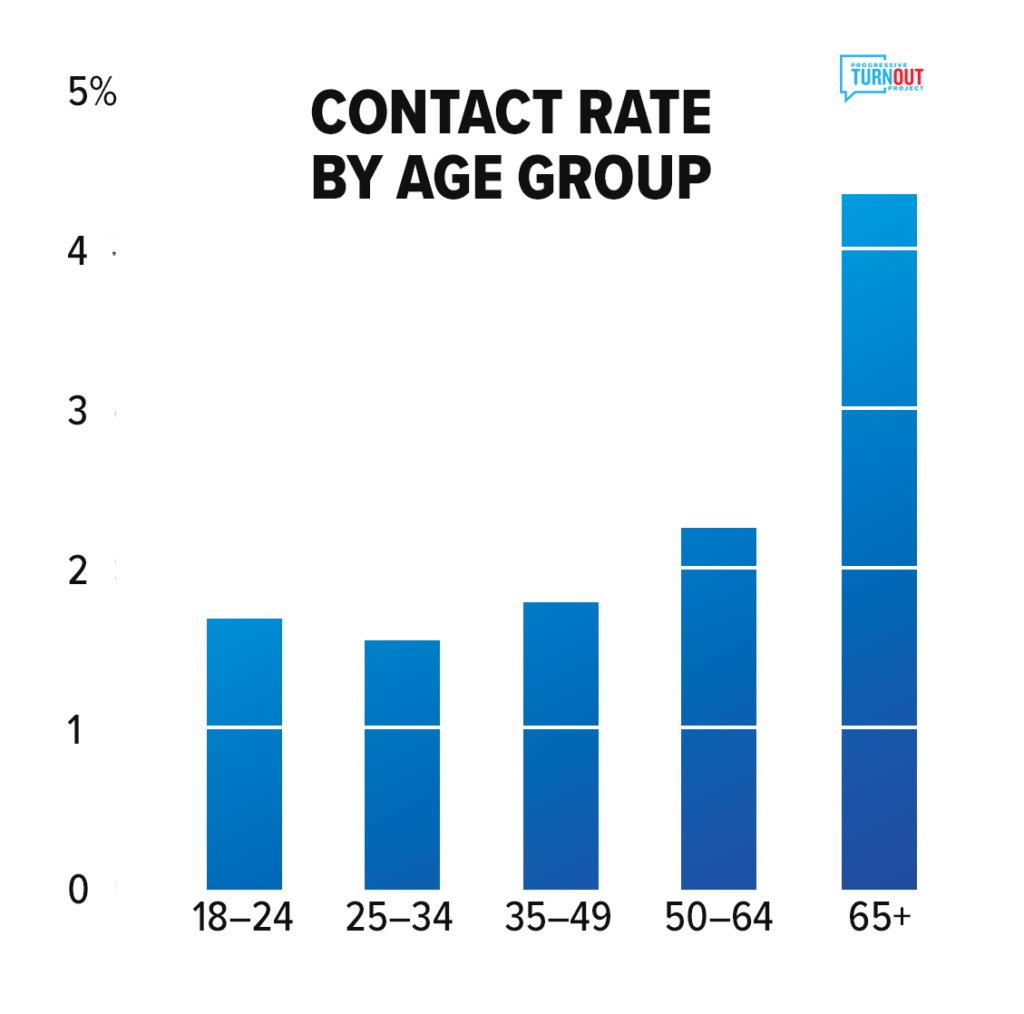

Another outcome, albeit less surprising, is that we found a significant correlation between age and contact rate. In simpler terms: older people answered the phone more. It was much more difficult to reach younger people than it would have been on the doors:

#2: The best time to contact people may not be when you think

Conventional wisdom dictated that we call on evenings and weekends, when people were more likely to be home.

But the pandemic changed a lot about when folks were free to answer the phone: many people started working remotely and stopped leaving their homes to socialize, dine out, or run errands.

Ultimately, we found that our calls typically performed better on weeknights than weekends. Across weeknight hours, there was not a large change in contact rate. But the earliest time we called, 4:00 pm local, did see a slightly higher canvass rate (successful conversations) and lower “not-home” rate than the other hours.

Folks on our staff were also concerned about calling from 8:00 to 9:00 pm. They worried it was too late at night and would turn off voters, especially older ones. The data did not bear this out. We did not find any significant difference in our refusal, contact, or not-home rate during the 8:00 hour compared to 7:00 or 6:00.

This may have been a lifestyle change limited to a pandemic situation — but even after the pandemic ends, it is important to re-examine the assumptions we lean on when determining a schedule for our program.

#3: Don’t waste your time on too many passes

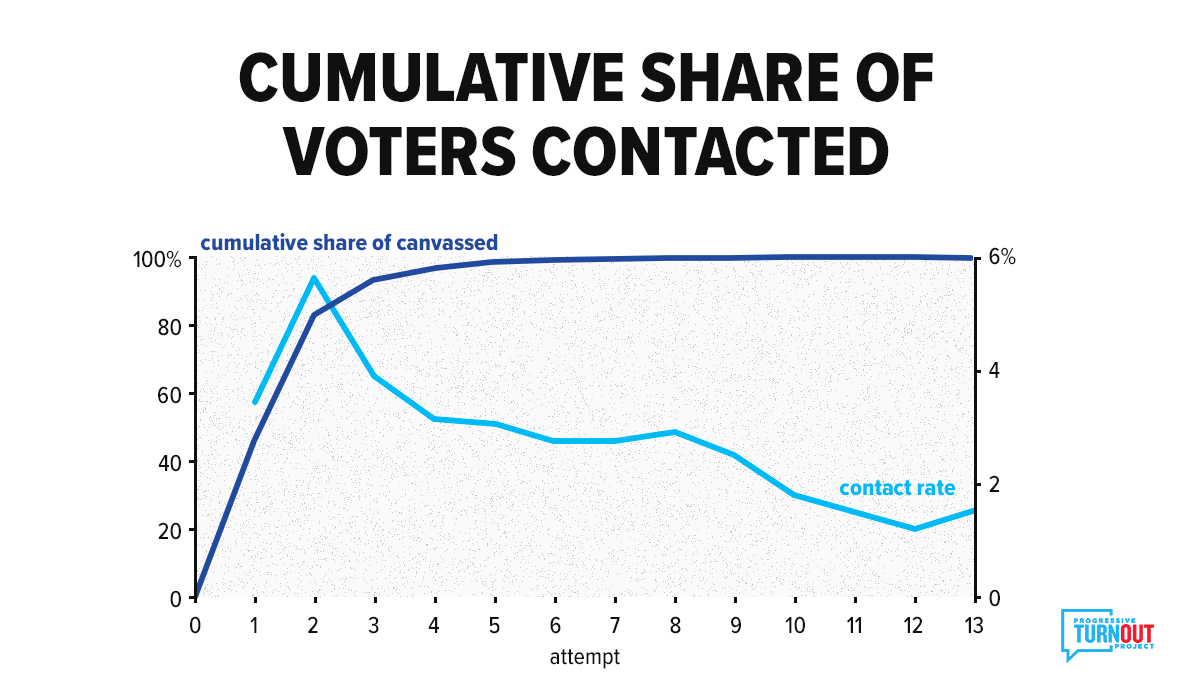

Because our phone universe was smaller than our calling capacity, and we wanted to maximize the number of voters we reached, we made several passes over our universe.

What felt true at the time was also proved by the data: after the third try, there are quickly diminishing returns on attempting the same targets over and over. With each pass, we reached fewer and fewer additional people, illustrated by a dropping contact rate. Ultimately, over 90% of the voter contacts we achieved were made within the first three tries.

Instead of trying to reach these targets who just wouldn’t answer the phone, we would have been better served by doing one of two things:

- Expanding our universe to reach different people. Attempting less-optimal targets would have resulted in more voters ultimately contacted.

- Making additional contacts with targets we already canvassed. Returning to the same, responsive voters would have reinforced our message and perhaps increased the chances they turned out to vote. We could even tie in an ask to encourage them to turn out their friends and families too.

#4: Balance quality conversations with efficiency

One of our phone scripts included walking voters through signing up to vote by mail — replicating the kind of high-quality conversations we’d aimed to execute on the doors. Our thought was that if we took the time to walk voters through this (often complicated) process, they would be more likely to request a ballot, and ultimately, vote.

But the data show otherwise. We did not see a significant increase in ballot requests among voters who got the walkthrough, compared to voters to whom we just texted the link for signing up. The walkthrough only boosted ballot requests from 64% to 68% — meaning we might have used those precious minutes to call different voters, instead.

Needless to say, we don’t want to live through another pandemic — or run another field program during one. Still, the experience did force us to reckon with some of our existing assumptions and learn new things.

In 2022 and beyond, rather than sticking with a static universe of targets who checked the boxes we thought were crucial, we will divvy up a broader, more diverse universe. Our goal should be to meet folks where they are, taking no target voter off the table.

We’ll also know when to cut our losses on another pass and instead drill down on targets we successfully contacted already. And we will think critically about balancing our desire for robust conversations with efficiency when it comes to scripts and asks.

And, while we cannot wait to get back on the doors, incorporating a wide breadth of tools and tactics (including phones) will be key to our success next cycle.

Some of our findings may be unique to the pandemic, like the best days and times to make calls, but others are good lessons to take with us as we plan our midterms program. By optimizing our scripts, revisiting our calling strategy, and segmenting our universes to reach different populations in different ways, we hope to turn out a record number of Democratic voters in 2022.

Interested in partnering with Progressive Turnout Project? Have questions about this blog post, or our work? Reach out to info@turnoutpac.org, addressing the note to Anastasia.